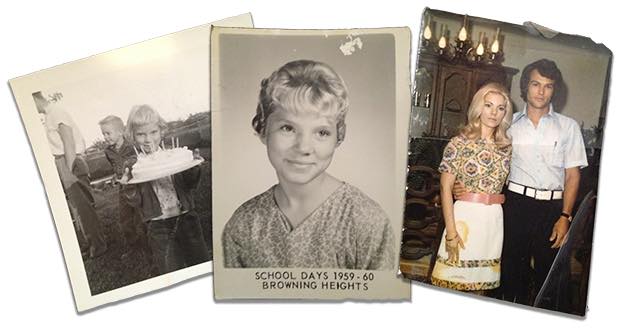

Memories of Momma - Part 6

Posted on Oct 5, 2019 (last modified May 30, 2021)

As I get older, memories become more and more like photographs instead of motion pictures. They age like old media - fading away like forty-five records and eight-track tapes. What were once, full color IMAX movies are now black and white flip-book photographs in a penny arcade. Old and worn, the pictures stick together in bent stacks - multiple frames skipping by under the goggles of an old hand-crank machine.

There's my grandfather's hand, twice as large as mine, thick and calloused - the hand of a working man. He holds it out for me when I enter the intensive care unit in the hospital and see Momma lying there.

Her eyes are open, but lifeless. They reflect fluorescent squares and cheap acoustic ceiling tiles. The sound of a mechanical pump pushes air into her lungs. A plastic tube, taped to the side of her face, slurps and gurgles as it pulls fluids from her mouth.

The lump in my throat is growing so large I feel I might choke on it. The taste in the air is not unlike formaldehyde.

A room full of family and yet I feel alone and lost and untethered from the world - as if floating away into the cold emptiness of space - into the vastness of it.

Grandpa must have seen me coming unmoored because then suddenly, there was his hand.

I reach for it, and take it - feel it swallow my own hand almost entirely. It is warm and alive and then, at once, I am back - tethered to the earth again. In the Vaseline periphery of my vision, my family comes into view - a circle around me and the body on the bed.

Steady beeps from a saline drip machine.

The stubborn little flip book sticks on that frame.

Close shot on her face - head shaven bald in just one peculiar spot...skin like plastic. My sister's voice in my ear, speaking some silly hope in miracles.

I can still see that one face. It's the one that erased all the others. That one sticky frame.

In twenty days I will dress for my wedding in the same hospital.

"You're going to be a grandma," I will say as I wrestle with a little cuff link. "You're going to miss it."

The accordion in the glass beside her bed will lift and fall, lift and fall, sounding like Darth Vader.

"If you don't come to," I will add. I know it's pointless, but I have to say it anyway.

"If you don't come to, you're going to miss it all."

A couple of weeks later, my stepdad will call.

"They're asking me to sign some papers," he will say.

I won't ask him to tell me what the papers say. Xerox copies on a clip-board - a bunch of fine print that bends and blurs through the pools in his eyes. In the dead silence on the phone, I will imagine him flipping numbly through the pages - staring vacantly at the empty space where he's supposed to sign.

"It's okay, dad. Sign the papers," I say.

Flipping forward, I pause on the frame where grandpa's sitting alone in Uncle Eddie's truck at the cemetery - the rest of us circled around grandma’s coffin. As they lower her into the ground, I look over there, but I can't see through the sunlight washing over the windshield.

There is wind in the trees. Birds chirping. I think it must be quiet over there in the truck. Lonely. Cold and quiet and lonely, like in outer space.

Here's a man who fought in a World War refusing to take his place in the circle around his wife's grave. I'm not sure why. Perhaps, he comes from a time too proud for men to cry. Or maybe he just wants to skip this shot; wise enough to know about sticky frames.

Still, I look at my hand, small and half covered by an over-sized jacket that I haven't worn in years. I feel like walking over there and getting in the truck with him. Shutting the door, sitting there in the silence, and maybe offering my own hand.

This pale, puny, sweaty hand. Not a callous on it.

I put it in my pocket and lower my head. Watch the casket go down.

Flip forward. Here's my daughter - artist like her dad - fighting to find her way in the world. Still just learning how to wield the fire of her own spirit. I don't worry that she keeps getting herself burned; that's the price of magic.

Her mother worries. I do not.

She feels the flame, but I see molten bronze and steel and gold flowing red-hot into the mold. I know what's being forged in there. I know what's coming out... in time.

The frames of my granddaughter bring back similar frames of my son. She looks just like him. In ten-seconds of Snapchat video that will be entirely gone tomorrow, she smiles at the camera and laughs - rocks gently back and forth in a motorized bassinet. I swear I took the exact same shot of my son twenty-four years ago. Those are sticky frames too.

I look at my hand again. Larger than hers - my little granddaughter's. Still larger than my children's, I think. Calloused now by time, if not by hard labor. Broken lines and lost frames and joints that get a little sore in the cold, if I'm being honest. But it's ready, this hand.

I hope it's big enough for them.